![]()

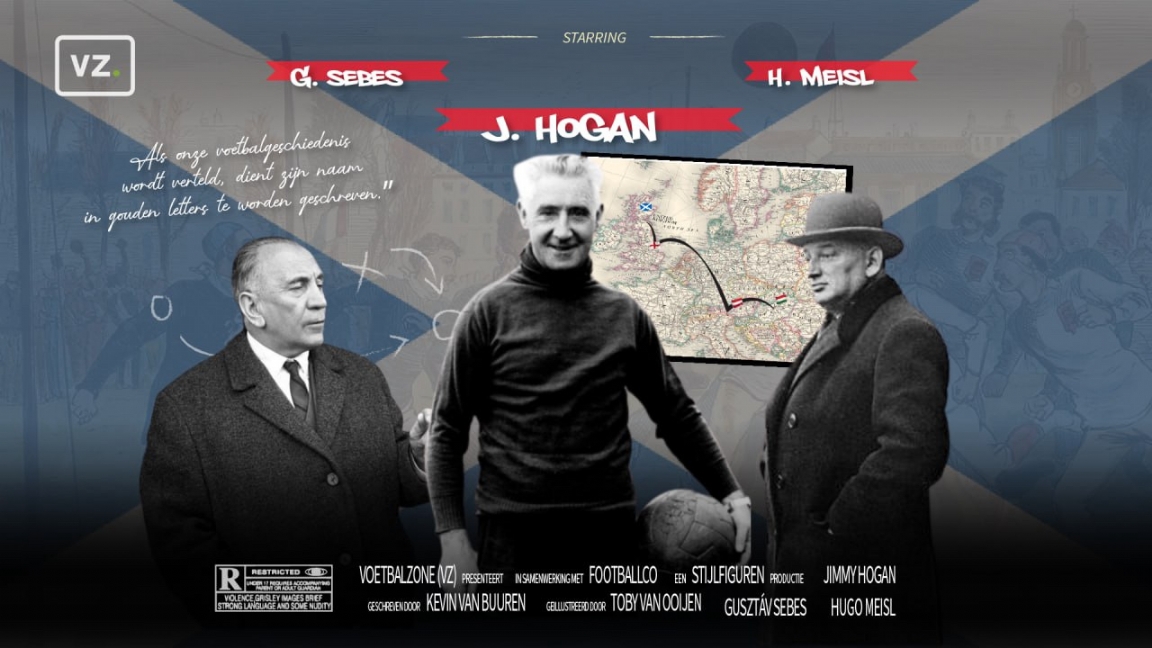

From total football to anti-football and everything in between. Winning the coveted three points has come in all shapes and sizes since time immemorial. In the section Style figures go Football zone along the fields of yesteryear to scrutinize fabulous formations and special positions. In this edition: the Scottish passing game. How the football nation today not known for refined field play sparked a philosophical football revolution.

Steven Gerrard is critical of the Scottish league. It is May 2019, the former captain of Liverpool has almost completed his first season as Rangers FC manager. “Sometimes competitions disappoint me. The stadiums are not full and the ball goes through the air very often,” he refers to the infamous kick and rush which apparently has not yet been eliminated from Scotland. For football-loving Europe, Scott Brown is also the symbol of Scottish football. The bald captain of Celtic is knocked over against Aberdeen in 2018, immediately stands up and cheers maniacally. Hots, clubs and enjoy.

The inventors

Nevertheless, in many history books, Scotland is the founder of modern football. The Netherlands likes to see itself as the inventor of total football, but that was not possible without Scottish influences at the end of the 19th century. Back then, football was even wilder than former Celtic midfielder Brown. The game consists of dribbling with the head down. Due to all the soloists, defenders are hardly needed. And those who are not in the front are expected to shoot the ball there as quickly as possible. Setups like 1-1-8 and 2-2-6 are not strange; it is visionless ball-in-goal. Until the Scottish intellectuals look into it.

Just as James Watt invents the modern steam engine in 1765 and economist Adam Smith lays the foundations for the free market economy, the Scots once made a team game of individualistic neanderthal football without vision. In 1872 Scotland and England compete against each other. The Scots, all playing for Queens Park club, are smaller and weaker than their opponents, forcing them to find other ways to win. Between 1878 and 1882, Scotland wins big against England three times with the revolutionary passing game. Not visionless, but philosophical. Functioning in harmony like parts of a steam engine, with the creative freedom of a free market.

From then on it spreads the Scottish passing game themselves about the world. After a visit to the Scottish Football Museum in Hampden, medium sums up The Scotman note: The first Liverpool team in 1892 was all Scottish. Charles Miller, son of a Scottish immigrant in Brazil, brought the artful game to Rio de Janeiro. There he laid the foundation for the known yoga bonito. School teacher Alexander Hutton taught the sport in Argentina and in Uruguay William Poole started the first club Albion FC. The Scottish way of playing is also responsible for the success of the Austrian in Central Europe Wonder team in the 30s. As well as the glory years of the Magic Magyars around 1950: Hungary. One name keeps coming up. Englishman Jimmy Hogan’s.

Dutch national coach for one day

Hogan still plays football in a time when training with the ball is taboo, Jonathan Wilson describes in Inverting the Pyramid. Players train their athletic abilities, but the ball is secondary. “Give a player the ball during the week, and he will crave it less on a match day,” is the motto. One day Hogan shoots high over after a good dribble. “How did that happen? Is my foot wrong? Was I off balance?” he asks his coach. Manager Spen Whittaker dismisses the questions. There is no theory in football. Hogan eventually arrives via Fulham, where the staff is filled with Scots, at Bolton Wanderers, with which he tours the Netherlands.

Coach Hogan (right) ensures a striking development in football: frequent training with a ball.

English teams don’t believe in coaching. Hogan therefore knows where his value lies: one day he will train players according to the Scottish way which he loves so much. When he wins 1-10 with Bolton against DFC in Dordrecht, he makes a promise: “I will come back one day to teach those guys how to play football.” That moment comes sooner than he thinks, when referee James Howcroft tells him that Dordrecht is looking for a trainer. Preferably a British one, because of the immense difference in level between the nations. Hogan denies the coincidence, applies and becomes a trainer at the age of 28. It is the first step of a football revolution in Central Europe, with the help of Hogan.

The brand new trainer is the first in the Netherlands to approach football in an almost scientific way. Like his philosophical predecessor Adam Smith, he creates a manual for the game of DFC. No dribbles, but passes. Don’t watch, but move along. Not eleven soloists, but a collaborative team. His methods also follow economic principles. A player needs to invest in himself through mercilessly hard, physical training. And by thinking. Hogan nestles his players in classrooms, where he will spend hours explaining the theory behind his game. Football is played on paper for the first time.

As a trainer, Hogan does not know how to fill the trophy cabinet of DFC. However, his innovative working method makes such an impression that he is allowed to lead the Dutch national team for one match. Hogan’s Holland beat Germany 2-1. After his work in Dordrecht, he briefly returns as a footballer at Bolton. Nevertheless, he is looking to the future as a trainer. Again referee Howcroft, known for his contacts in the football world, is decisive. He puts Hogan in touch with Hugo Meisl in Austria. Fellow referee and future national coach of the country.

Wunderteam Austria

Before Meisl meets Hogan, he works for the Austrian Football Association. After a disappointing draw, he asks his friend and the referee on duty, one James Howcroft, what his team should do better. “A good trainer who improves their technique”, is the answer. And Howcroft knows someone. Meisl has set itself the goal of putting Austrian football on the map. Although he doesn’t know exactly how yet, he will find a way. Ultimately, Hogan will never become national coach of Austria. Meisl observes those honors herself between 1919 and 1937. Hogan does help shape football in Austria, with a focus on technique, targeted long passes and, above all, many short passes. As he once learned with wonder from the Scots.

On the basis of that way of playing, Austria was undefeated in international football between April 12, 1931 and December 7, 1932. It Wonder team, the best football team in Europe, was narrowly defeated by England on December 7. Although the inventors of football won 4-3, all eyes were on the Austrians, who played the game as the football gods must have intended. “Football became an exhibition, a kind of competitive ballet, in which scoring goals was nothing more than an excuse for weaving complex patterns,” English writer Brian Glanville described that wondrous team.

It Wonder team defeated France 3–2 in the quarterfinals at the 1934 World Cup.

The Magic Magyars

Twenty years later, more than 500 kilometers further, football continues to develop in Europe. Hogan had many interim jobs, training for the success of Austria Aston Villa, Celtic and even a small club in Budapest: MTK. In 2014 he introduces his Scottish way of playing at this club, then and there baptized the Danubian style. Named after the Danube; river Danube. His influence will only be felt years later, when Hungary conquers the football world in the 1950s. The success of the Hungarian national team begins with a 12-0 victory over Albania in September 1950. Two years later, the team wins the 1952 Summer Olympics in Helsinki. Led by Ferenc Puskas, who in 2009 will be named the prize for the most beautiful goal of the year.

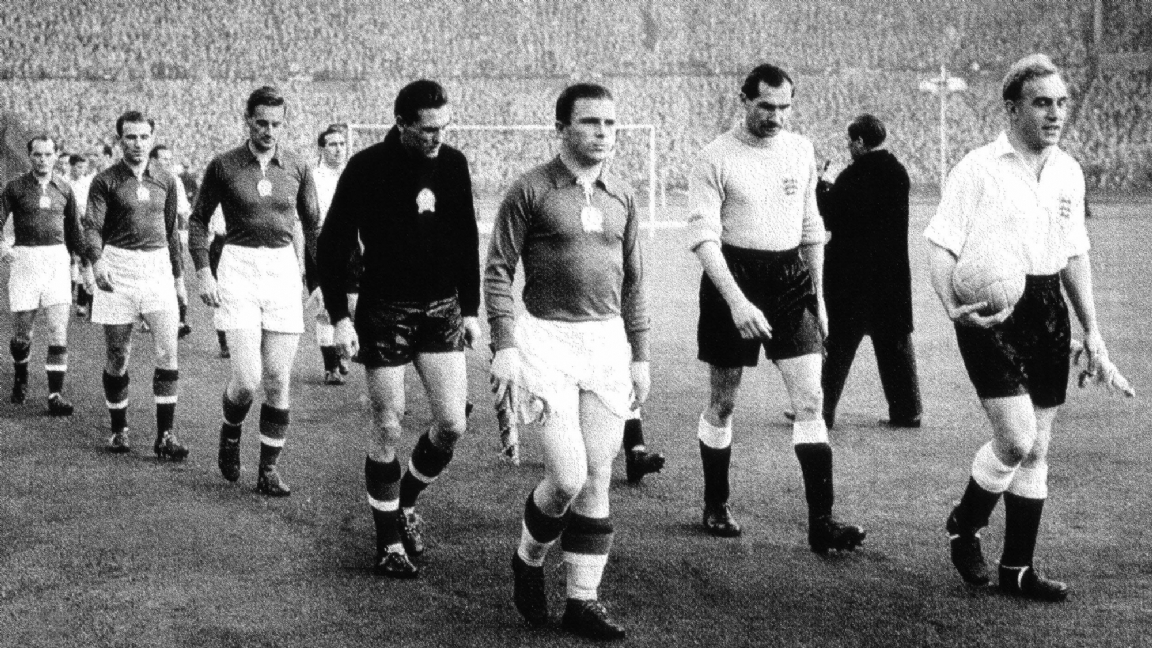

The most memorable match, however, takes place a year later. On November 25, 1953, England received the Magic Magyars, as the success team goes through life after being undefeated for three years. The match will later be labeled as the match of the century. For sporting and political reasons. “The bitter battle between capitalism and communism is fought not only within our peoples, but also on the field,” said Hungarian national coach Gusztav Sebes. Winning against football pioneer England was the measure of success at that time. Hungary wins no less than 3-6. Success coach Sebes thought of one man after the legendary victory: Jimmy Hogan. “We played football the way Hogan taught us. If our football history is told, his name should be written in gold.”

England and Hungary take the field for the ‘match of the century’.

The big three

In what seems like a parallel universe today, Scotland, Austria and Hungary are the big three of modern football. All those countries bow to what Jonathan Wilson calls ‘the most influential trainer ever’: James ‘Jimmy’ Hogan. The late Tommy Docherty, Scottish football coach and former pupil of Hogan when the Englishman trained Celtic, described to BBC: “He saw football as a Viennese Waltz; a hymn: one-two-three, one-two-three, pass-move-pass, pass-move-pass.”

If Austria is busy it is Wonder team to put on the map, Hogan also spends time in Germany, know Football International. Building up the youth academy and spreading his philosophy, he is also called ‘the founder of modern German football’ there. Short passes, movement and creativity. The game that made the Netherlands big in the 1970s under the name of total football. That story, too, could never be told without the laying of that first puzzle piece by Hogan: the Enlightenment philosopher of modern football.